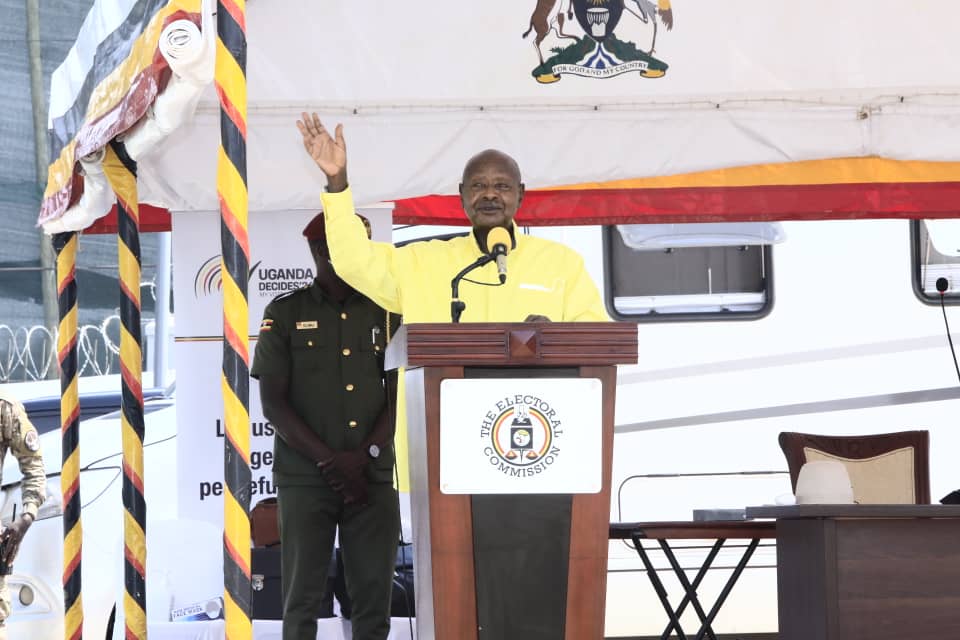

The mood at the new Electoral Commission (EC) headquarters today in Lweza was quiet. At 10 am, President Museveni, aged 81, arrived with First Lady Janet Museveni. With a few aides and security guards, he handed in his nomination papers as the National Resistance Movement (NRM) candidate for the January 2026 election.

Justice Simon Byabakama, the EC boss, quickly approved his papers, saying everything met the Presidential Elections Act. There were no loud cheers apart from the brief chants by Prime Minister Robinah Nabbanja or big crowds. No bands played victory songs. Just a few journalists, officials, and supporters stood under tents. It was all done in less than an hour.

This quiet event marked the start of the presidential nominations, which end tomorrow. But across Uganda, the mood feels dull. In the past elections—2001, 2006, 2011, 2016, and even 2021—these moments brought huge rallies with thousands of people.

Opposition leaders like Dr Kizza Besigye pulled big crowds, and NRM supporters matched their energy. Streets were full of posters, chants, and lively debates. Today? Social media posts from Kampala to Gulu are short and boring. Taxi drivers don’t care much. Shopkeepers and vendors in busy markets like Owino barely know what is going on.

So, why is the excitement gone? It is mainly because many people feel tired and the political system seems one-sided, in favour of President Museveni and the NRM. Many Ugandans, especially the youth who make up over 70% of the population, see the election as just a routine, a “walkover” for Museveni, as one expert said. He has been president since 1986, longer than most voters have been alive. Polls show the NRM still has support, but trust in the election system is fading fast.

One big issue is the opposition’s struggles. Parties like the National Unity Platform (NUP), led by Robert Kyagulanyi aka Bobi Wine, were cleared for the nominations after some ping-pong with the EC. The opposition is also split: new small groups keep popping up, weakening their votes, while older ones like the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC) are a shadow of their former selves. Critics say the opposition lacks a clear plan or enough money to challenge the NRM’s strong machine.

“They are weak and divided,” said NRM’s former vice chairman for Eastern Uganda, Capt Mike Mukula. Without a strong alternative, people lose interest. Indeed, a recent survey by Afrobarometer showed most Ugandans support multiparty democracy but feel the opposition offers no real change.

Another problem is the shrinking space for democracy. It is harder now to speak freely, protest, or organize. Tough laws, like the 2022 Computer Misuse Act, make online criticism a crime. As the 2026 election period starts in earnest, soldiers have started patrolling the streets, and there is talk of tracking social media.

“It’s like an electoral dictatorship,” noted Democracy in Africa, a think-tank, in their recent assessment of the political environment in Uganda.

For many, speaking out feels dangerous. Why join a rally if it could land you in Luzira Prison?

This gloom has led to hopelessness. On the streets, in the pubs, or at social functions, it is not uncommon to hear people say, “Museveni will win anyway. Why bother?” Economic problems make it worse. Youth unemployment is at 13%, food prices are rising, and corruption scandals destroy trust. Past elections had low turnout. In 2021, voter turnout was 59%, down from 68% in 2016. Experts think 2026 could be even lower, with many disillusioned people staying home.

Still, there’s some hope. Kyagulanyi’s eventual clearance by the EC has excited NUP supporters, showing some fight remains.

After being nominated today, Museveni said that Uganda has “changed” with new jobs in oil and tech. But for young people who want more than just stability, the 2026 election already feels like watching an old movie with the same ending.

The big question is: Will enough people show up to change the story?