If you are a heavily indebted businessperson in Uganda, sinking under the weight of a bank loan with no hope of repaying it, what do you do?

For many, they would let the bank foreclose their mortgaged properties and lick their wounds.

But if you are of the stature of Hamis Kiggundu, Patrick Bitature, Amos Nzeyi, or the late Peter Kamya (of Simbamanyo Estates), you would turn to Fred Muwema, the astute, or as some would say, shrewd lawyer, who has been a mainstay on the legal scene for the last 25 years.

As the legal representative of several city tycoons battling to repay bank loans, Muwema has become synonymous with pulling “the rabbit out of the hat,” as some would call it by putting forward the argument that: “The foreign lenders are not registered under the Financial Institutions Act and therefore lack the legal standing to enforce loan agreements.”

In some cases, this tactic has brought him wins; in others, it has sparked controversies, cementing his status as a polarizing figure in Uganda’s legal and banking sectors.

Legal titan

Muwema’s journey to prominence began with the establishment of Muwema & Mugerwa Advocates & Solicitors in October 1998. He co-founded it with his law classmate Herbert Kiggundu Mugerwa.

At its height, the firm handled many high-profile cases and had a clientele that included Orient Bank, Shell Uganda, British American Tobacco Uganda (BATU), and Mike Mukula.

However, in 2014, the firm was dissolved after the senior partners developed irreconcilable differences. Muwema went his separate ways and formed Muwema & Co. Advocates, headquartered in the leafy suburb of Kololo along Windsor Crescent Road.

One of his first top clients was Amama Mbabazi, the former prime minister, after he broke political ranks with President Museveni in 2014.

Their legal relationship, however, lasted only two years after Muwema conspicuously pulled out of the Supreme Court petition Mbabazi had lodged challenging Museveni’s victory at the 2016 polls. On the eve of the start of the hearing of the case, Muwema’s offices were allegedly broken into, and some crucial files were taken.

In the same year, Muwema made headlines by filing a groundbreaking case against Facebook in Ireland, in which he sought to force the social media giant to reveal the identity of Tom Voltaire Okwalinga, aka TVO, who alleged on his popular Facebook page that Muwema had colluded with Museveni to defeat justice in the Amama Mbabazi court case.

An Irish court dismissed Muwema’s application.

Saviour of indebted tycoons?

Yet Muwema’s most prominent stage has been his representation of indebted businessmen in high-stakes loan disputes with financial institutions.

His clients, often prominent tycoons like Hamis Kiggundu, Patrick Bitature, and the late Peter Kamya of Simbamanyo Estates, share a common predicament: defaulting on substantial loans, often from foreign lenders.

Muwema’s signature strategy is to challenge the legality of these loans by arguing that foreign banks, such as Diamond Trust Bank (DTB) Kenya or Equity Bank Kenya, are not registered under the Financial Institutions Act, rendering their lending activities in Uganda unlawful.

This approach was most notably deployed in the Ham Enterprises vs. Diamond Trust Bank case, a landmark dispute that sent shockwaves through Uganda’s banking sector. In 2020, Muwema represented Hamis Kiggundu, who accused DTB Uganda and DTB Kenya of illegally withdrawing over Shs120 billion from his accounts without consent.

Muwema argued that DTB Kenya, as a foreign bank, lacked authorization from the Bank of Uganda to conduct financial business in Uganda, violating the Financial Institutions Act. He further contended that DTB Uganda acted unlawfully as an agent for its Kenyan parent.

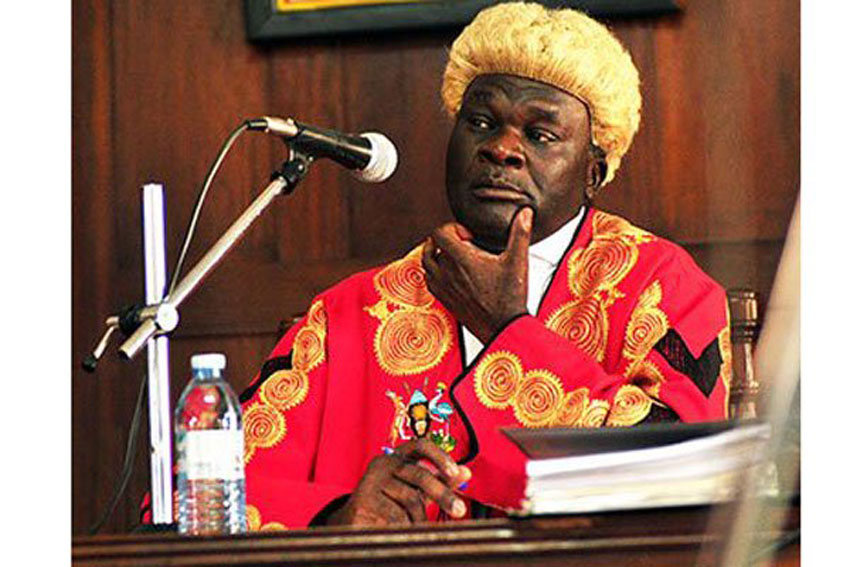

In a stunning victory, Justice Henry Peter Adonyo of the commercial division ruled in Kiggundu’s favor in October 2020, declaring the syndicated loan illegal and ordering DTB to refund the deducted funds and return Kiggundu’s securities.

The ruling sparked uproar, with the Uganda Bankers’ Association (UBA) labeling it “reckless” and warning of risks to a Shs5.7 trillion syndicated loan portfolio. Muwema hit back, accusing the UBA of spreading misinformation and undermining judicial independence, further fueling the controversy.

But the triumph was short-lived. In May 2021, the Court of Appeal overturned the High Court’s decision, directing the case to be heard afresh. By 2023, the case had escalated to the Supreme Court, where Muwema sought judgment based on DTB’s alleged admission of operating without a licence. Despite the initial victory, the higher courts’ rulings exposed the limitations of Muwema’s technical argument, with the Bank of Uganda clarifying that foreign banks lending without taking public deposits do not fall under its regulatory purview.

Yet the saga, still unresolved as of today, showcased Muwema’s ability to disrupt the financial sector, even if his legal gambit did not always secure lasting victories.

Simbamanyo, Bitature battles

Muwema’s strategy faced further scrutiny in other high-profile cases. In the Equity Bank vs. Simbamanyo Estates dispute, Muwema represented Simbamanyo Estates, owned by the late Peter Kamya, in a battle over a $6 million syndicated loan from Equity Bank Uganda and Equity Bank Kenya, followed by a $10 million bridge loan facilitated by Bank One in 2017. When Simbamanyo defaulted, Equity Bank moved to auction properties, including Simbamanyo House and Afrique Suites Hotel.

Muwema argued that the involvement of Equity Bank Kenya and Bank One was illegal, as they were not licensed in Uganda, and accused the banks of predatory practices and breach of trust. He sought to halt the sale, alleging fabricated charges and undue influence.

Despite securing a temporary injunction, Muwema’s arguments were ultimately rejected. In a ruling last month, Justice Harriet Grace Magala upheld the validity of the loan transactions, stating that the syndicated arrangement was a commercial necessity and that foreign bank lending did not violate the Financial Institutions Act unless sourced from public deposits.

High Court: Equity Bank ‘legally’ sold Simbamanyo House to Sudhir

The properties were sold to tycoon Sudhir Ruparelia’s Meera Investments and Luwaluwa Investments, closing a contentious chapter.

In this case, Muwema’s technical argument, while bold, failed to sway the court, underscoring the judiciary’s growing skepticism of his reliance on regulatory technicalities.

Similarly, in the Bitature vs. Vantage Mezzanine case, Muwema represented businessman Patrick Bitature, who borrowed $30 million from Vantage Mezzanine Fund II, a South African firm, in 2014. When Bitature defaulted, Vantage sought to recover the loan through private prosecution.

Muwema attempted to block this by seeking an injunction, arguing that Vantage was not registered in Uganda. However, in May 2022, Justice Stephen Mubiru dismissed the application for lacking a legal basis and ordered Muwema to personally pay costs, citing his failure to competently advise his client.

The ruling was a rare rebuke, highlighting the risks of Muwema’s aggressive legal tactics.

Criticisms

Muwema’s reliance on the unregistered-lender argument has drawn significant criticism. Critics argue that his strategy exploits legal loopholes to delay or evade loan repayments, potentially tarnishing Uganda’s reputation as an investment destination.

In the Ham vs. DTB case, the ministry of Finance and the Bank of Uganda publicly criticized Kiggundu’s actions, with the latter asserting that foreign lending without public deposits is permissible.

The Uganda Bankers’ Association accused Muwema of promoting “fake news” and undermining the banking sector’s stability. These criticisms paint Muwema as a provocateur, prioritizing technical victories over the substantive issue of his clients’ financial obligations.

Moreover, Muwema’s approach has occasionally backfired. The Bitature case’s cost order against him personally was a public humiliation, with Justice Mubiru emphasizing that competent legal advice could have avoided unnecessary litigation. Similarly, the Simbamanyo case’s outcome reinforced the judiciary’s reluctance to invalidate loans based solely on the registration status of foreign lenders.

These setbacks have fueled perceptions that Muwema’s tactics, while creative, sometimes prioritize theatrics over substance.

Despite these controversies, Muwema’s triumphs are undeniable. His ability to secure initial victories, as in the Ham vs. DTB case, demonstrated his legal acumen and tenacity.

Others say by representing high-profile clients, Muwema has amplified the voices of businessmen like Hamis Kiggundu, who claim exploitation by powerful financial institutions.

For Uganda’s indebted tycoons, Muwema remains the lawyer of last resort, a master at conjuring legal rabbits out of hats. His “unregistered-lender argument”, while not always successful, has disrupted the status quo, challenging banks to clarify their operations and regulators to tighten oversight.