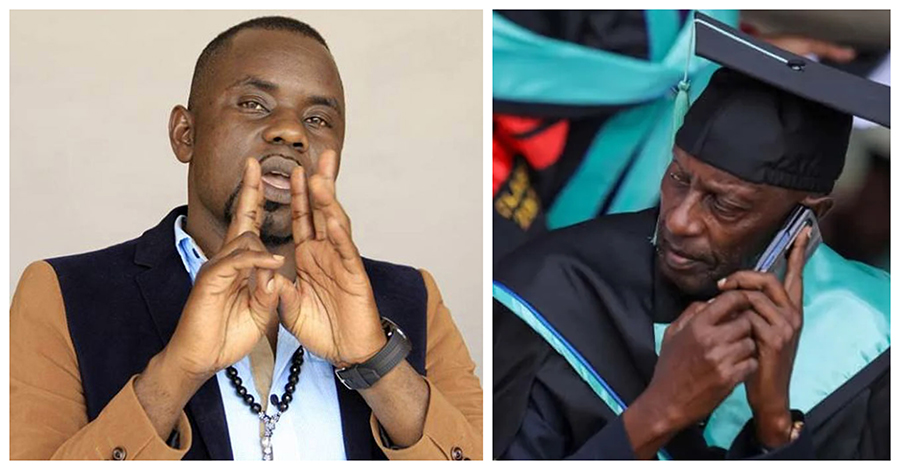

The decision by the Electoral Commission (EC) to throw Mathias Walukagga out of the Busiro East race for lacking the minimum academic qualifications has led to a heated public debate on whether or not he was treated fairly.

Critics of the EC have pointed out that a few days before Walukagga was denominated, the commission upheld the nomination of Brig. Emmanuel Rwashande from Lwemiyaga, whose academic papers, too, had been questioned.

However, a closer look at the two cases reveals that they were different on legal and factual grounds. Here is how.

In Walukagga’s case, the EC said he did not meet the minimum academic requirements to be a Member of Parliament. The law requires a candidate to have completed A-level or its equivalent. In Walukagga’s case, the commission said the documents he submitted did not prove he had attained that qualification.

Petitioners had argued that the singer’s academic history was unclear and that the certificate of Mature Entry from the Islamic University in Uganda (IUIU) that he submitted could not be equated to A-level. In its ruling, the commission agreed. It said it had reached out to the relevant education bodies like the National Council for Higher Education (NCHE), but failed to obtain confirmation that Walukagga’s papers were genuine.

Without that verification, EC said it was legally bound to remove him from the race. So the decision was a matter of evidence rather than politics, as some people had claimed.

Rwashande’s case was different, even if it centred on his academic qualification. His qualifications had also been questioned, with his opponent Theodore Ssekikubo arguing that he did not meet the A-level requirement. But when the EC examined his documents, it found that his academic record could be traced and verified.

Officials said the institutions where he studied confirmed that he had completed the necessary level of education. Though Ssekikubo insisted that some documents were inconsistent, the commission said the discrepancies were minor and did not invalidate the core evidence of his qualification.

Therefore, the key distinction between the two cases was the availability and reliability of verification of the academic documents. In Walukagga’s case, the commission said it had no credible proof that he possessed the required A-level certificate. In Rwashande’s case, the commission said it received written confirmation from the issuing schools and authorities, making his papers legally sufficient.

How Mathias Walukagga’s disqualification has reshaped the Busiro East race

The second difference lay in the burden of proof. The commission treats academic qualification complaints as factual issues. Petitioners must show that a candidate’s documents are invalid. In Walukagga’s case, the doubts raised were reinforced by the commission’s inability to authenticate his papers from the institutions he claimed to have attended. In Rwashande’s case, the doubts were weakened by confirmations from school authorities.

Those are the major differences between the two cases.