President Museveni has dominated Uganda’s political scene for nearly four decades. This is not news.

Here is what is: During this time, a pattern has emerged within the National Resistance Movement (NRM), a party that he leads and shepherds like a personal kiosk: prominent figures face humiliation, demotion, or even legal troubles, yet they rarely break away permanently.

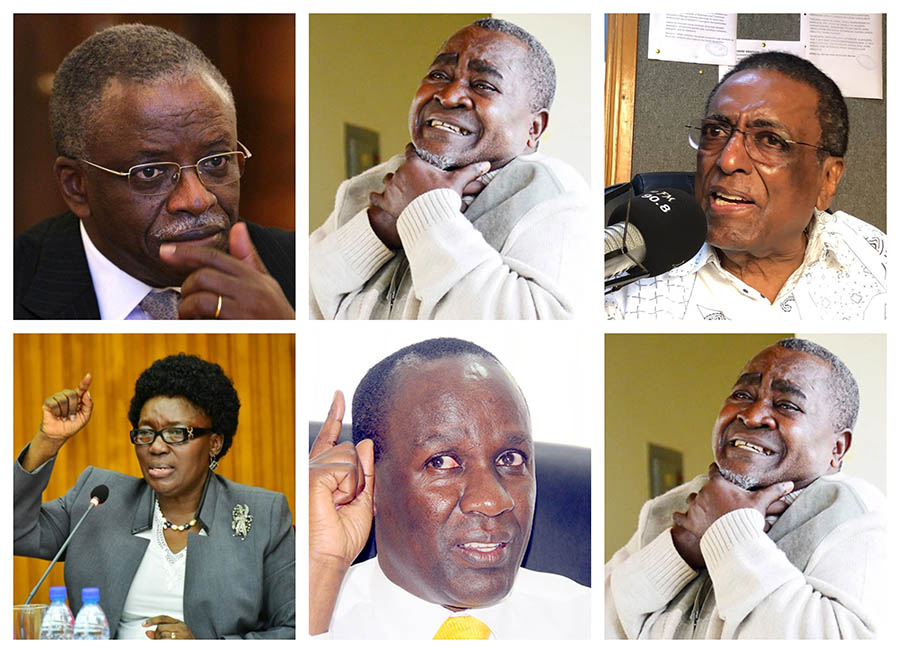

Take Rebecca Kadaga, the former Speaker of Parliament and current First Deputy Prime Minister. Just days ago, she suffered a crushing defeat in the Central Executive Committee (CEC) elections, losing to Speaker Anita Among by a wide margin.

Despite voicing frustration over being sidelined after years of service, Kadaga quickly reaffirmed her commitment, pledging to uphold NRM values and principles.

This isn’t isolated. Amama Mbabazi, once Museveni’s trusted ally and prime minister, dramatically fell out in 2014 when he announced plans to challenge the president in the 2016 elections. After a bitter campaign, Mbabazi returned to the NRM fold by 2020, agreeing to collaborate with Museveni again.

Similarly, Mike Mukula and Jim Muhwezi, former health ministers, were embroiled in the 2006 Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation (GAVI) funds scandal, facing charges of embezzling millions, brief imprisonment, and unceremonious cabinet dismissals. Yet both were acquitted in later years and now openly support the NRM.

Prof Gilbert Bukenya, the former vice president, spectacularly fell out with Museveni when he was dropped from cabinet after the 2011 elections. Bukenya even alleged that his son, Brian, had died under mysterious circumstances. He is now a senior presidential advisor on the environment.

Edward Francis Babu, a veteran NRM cadre, has grumbled about internal injustices—like being forced to step aside for Moses Kigongo in a 2020 party race—but remains within the party, criticizing its direction while staying loyal.

These cases raise a simple question: Why do these politicians endure perceived unfairness but can’t jump ship?

Experts and observers point to a mix of fear, financial incentives, and self-preservation, all rooted in the NRM’s iron grip on power.

The Besigye Lesson

One major deterrent is the specter of harsh reprisals from Museveni and the state apparatus. The most cited cautionary tale is Dr Kizza Besigye, Museveni’s former personal doctor and a bush war comrade, who broke ranks to challenge him in the 2001 presidential election. What followed was a relentless campaign of persecution: Besigye fled into exile in South Africa in 2001, citing threats to his safety.

Upon returning in 2005, he was arrested on treason and rape charges, which many viewed as politically motivated. Over the years, Besigye has faced repeated detentions, house arrests, and trials, including a recent 2024 abduction in Kenya that led to his deportation and further charges in Uganda. He is still holed up in Luzira Prison where he has spent more than 10 months.

This pattern of “partisan law enforcement” and “lethal force against opposition” has become a hallmark of Museveni’s rule, according to analysts. For NRM insiders like Kadaga or Mbabazi, defecting could mean similar treatment. There could be loss of protection, fabricated cases, or worse. As one report notes, Museveni uses “legal means and state coercion to suppress” dissent, making exit risky.

Financial Security

Another key factor is the NRM’s control over state resources, which provides financial stability and perks that are hard to abandon. Loyalty to Museveni and the NRM is often rewarded with jobs, contracts, and funding. The party retains power through “patronage, intimidation, and politicized prosecutions,” ensuring members benefit from government positions.

For figures like Mukula and Muhwezi, their “rehabilitation” came with continued access to NRM networks. Mukula, in particular, returned as a vocal supporter, likely preserving his influence in business and politics. Mbabazi’s family has even reintegrated, with his wife Jacqueline elected to an NRM elders’ position in 2025.

Therefore, leaving Museveni or the NRM means forfeiting these benefits in a country where the NRM dominates the economy and institutions. As one observer put it, party members “ride the presidential coat-tails” for electoral and financial gains.

Kadaga’s situation illustrates this: Despite her recent loss, she holds a ministerial role, which offers salary, security, and status. Quitting could strip her of these, especially in a system where opposition figures struggle financially.

Self-Preservation

At its core, staying is often about self-preservation. Many of these politicians are “too weak to stand on their word,” as critics suggest, fearing isolation in a multiparty system that favours the NRM. Museveni’s failure to build strong institutions for the country and party has created a personal cult, where loyalty to him trumps ideology.

Former defectors like Mbabazi found opposition life tough (it was reported that Museveni had at one point paid tuition for some of Mbabazi’s grandchildren in one of the international schools). Mbabazi’s 2016 bid weakened the NRM temporarily but failed, leading to his return.

Some say historical ties also play a role. Some like Muhwezi, are bush war veterans who owe their careers to Museveni. Breaking away feels like betrayal, and with no strong alternative parties, it’s pragmatic to complain internally rather than exit

As Babu recently noted, the NRM has been “infiltrated” by opportunists, but he advocates reform from within.

Museveni’s “stranglehold,” on the NRM and country illustrates Uganda’s competitive authoritarianism: elections exist, but real power lies with Museveni.

While figures like Kadaga may protest unfairness, they will ultimately seek reconciliation. They are like an angry partner who constantly threatens to leave a marriage but somehow, they can’t.