The High Court in Mpigi has ordered a DNA test to determine whether Sylvia Nampijja is the biological daughter of the late Robert Kaweesi, in a bitter family dispute that has stalled access to his estate and pitted his alleged widow against a young woman claiming to be his child.

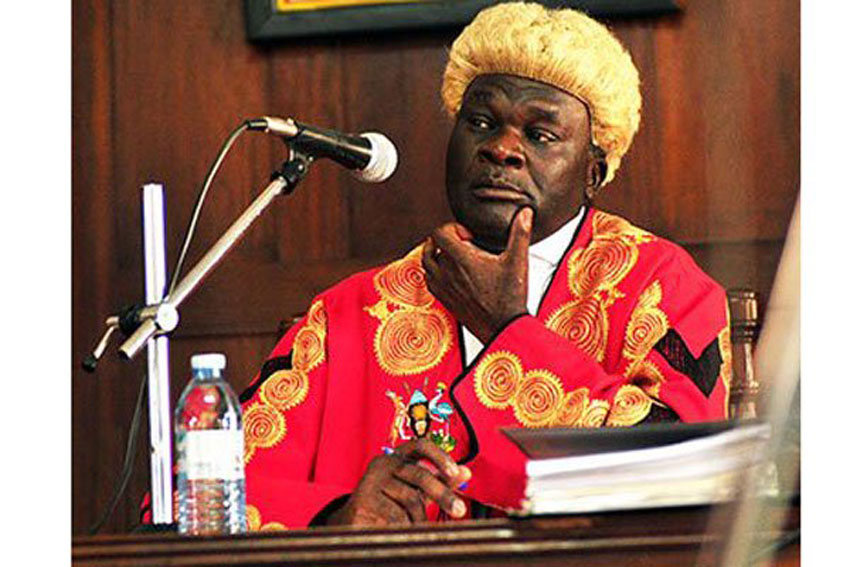

Justice Anthony Oyuko Ojok, in his ruling, partly allowed an application filed by Justine Katantazi, who says she was married to Kaweesi and has three minor children with him, but rejected her request to exhume the body of the deceased for DNA testing.

The dispute arose after Kaweesi’s death, when Nampijja filed a civil suit in May 2024 claiming she was his biological daughter and a rightful beneficiary of his estate.

She asked court to recognise her as such and award her general damages, while also challenging Katantazi’s marriage to the deceased.

Katantazi responded by filing a separate application asking court to order a DNA test to conclusively determine Nampijja’s paternity.

She also asked for permission to exhume Kaweesi’s body to obtain DNA samples, or in the alternative to exhume the body of Pascal Ssengaba, whom she claimed was Nampijja’s true biological father.

Katantazi told court that the dispute had paralysed the administration of Kaweesi’s estate.

She said she had lodged a caveat and could not obtain letters of administration until the question of who the lawful beneficiaries were was settled.

According to her, the estate was being wasted while her three children, all below 18, were at risk of failing to afford their school fees and financial support.

Katantazi argued that Nampijja was not Kaweesi’s daughter.

She claimed Nampijja was actually the child of the late Pascal Ssengaba, but that Kaweesi had assisted her to process travel documents and later stay with him in Birmingham in the United Kingdom.

She insisted that a DNA test was the only way to clear the uncertainty surrounding the estate and end the multiple court cases.

Nampijja strongly opposed the application.

She told court that she was the biological daughter of Kaweesi and relied on what she described as her birth certificate showing him as her father.

She argued that during his lifetime, Kaweesi never questioned her paternity and lived with her in Birmingham.

She further claimed that Katantazi had no legal standing to question her paternity and that subjecting her to a DNA test would violate her rights.

Nampijja also objected to the proposed exhumation of Kaweesi’s body, calling it unjustified, emotionally harmful and an abuse of court process.

Her lawyers argued that the application was brought in bad faith and was intended to embarrass and harass her.

They also attacked Katantazi’s status, claiming there was no valid marriage between her and the deceased, or that if it existed, it should be declared null and void because of alleged irregularities.

Karim’s hotel got Shs 8.7 bn for CHOGM rooms. It didn’t deliver and has been fined Shs 5.6 bn

Justice Oyuko framed two issues for determination.

The first was whether Katantazi had the legal standing to challenge Nampijja’s paternity.

The second was whether the court should order a DNA test, including through exhumation of the deceased.

On the issue of standing, the judge ruled firmly in Katantazi’s favour.

He noted that Katantazi was the mother of three undisputed biological children of the late Kaweesi, all of whom were minors.

“The children being below 18 years cannot therefore apply to obtain Letters of Administration and this can only be done by their mother who has custody,” Justice Oyuko said.

He added that the respondent did not deny the paternity of these three children.

This, the court said, gave Katantazi a direct and legitimate interest in the estate and in determining who else could lawfully benefit from it.

The court then turned to the question of evidence.

Justice Oyuko subjected Nampijja’s claimed birth certificate to close scrutiny and found it wanting.

He noted that the document was only a photocopy, was neither original nor certified, and had no confirmation from the Uganda Registration Services Bureau (URSB) or the National Identification and Registration Authority (NIRA).

“It is not supported by any other documents like a baptism card, school or medical records,” he observed.

Justice Oyuko further pointed out inconsistencies in Nampijja’s names across her documents.

While the birth certificate bore three names, later documents such as her passport carried only two, with no deed poll or statutory declaration explaining the change.

Justice Oyuko emphasised that under the Children’s Act, the burden of proving parentage lies on the person alleging it.

He said while a certified birth record creates a presumption of paternity, that presumption can be displaced by contrary evidence, including DNA testing.

He described DNA testing as “nearly 100 percent accurate” and “a clearer and more concrete process of proving paternity than witness testimonies and statements in the register.”

However, on the question of exhuming the deceased to determine paternity, Justice Oyuko declined.

He stressed that the law strongly disfavors disturbing a buried body.

“A ‘decently buried’ body should remain undisturbed unless good reason is given,” he said.

He noted that exhumation is emotionally sensitive and must be justified by compelling reasons. In this case, the court found that such extreme measures were unnecessary.

Instead, Justice Oyuko ruled that a sibling DNA test could be conducted using samples from Kaweesi’s three undisputed children to determine whether Nampijja shared the same biological father.

In the final orders, the court directed that Nampijja undergo a DNA test alongside the three children of Katantazi.

The samples are to be taken at a recognised laboratory either in Birmingham or Kampala within one month. He said the testing process must be monitored by both parties to ensure transparency, and the results must be sent directly to the Mpigi High Court.