Mustafa Kangave had worked at Pride Microfinance for 16 years and had risen through the ranks to become manager at their Nakawa branch.

However, on March 2, 2019, he was arrested and detained at Kabalagala Police Station after a complaint lodged by socialite and businessman Brian White. Brian White alleged that an unspecified amount of money meant for him had gone missing at the branch.

For nine days, between March 2 and March 11, Kangave was pressed by the police about Brian White’s money. He denied taking any money and insisted he had no role in the alleged loss.

After being released without charge, he went back to work and expected that the matter would be resolved through formal processes.

On March 22, 2019, Pride Microfinance’s head of human capital management wrote to Kangave. The letter invited him to a meeting scheduled for March 25.

It read: “Following allegations regarding receipt of funds from Bryan White and your subsequent arrest and detention at Kabalagala Police Station for the period March 2nd to 11th 2019, management is hereby inviting you for a meeting to explain issues surrounding this case.”

The letter did not accuse him directly of theft or misconduct. It did not mention disciplinary charges. It did not inform him of his right to be accompanied by another employee or a representative. It simply asked him to appear.

At the meeting, Kangave gave both a written statement and an oral explanation. The bank then asked him to go to the police and obtain a formal clearance to show that the investigation against him had ended. He was given until April 1 to obtain the letter of clearance.

Before he could get the clearance, the bank terminated his contract.

Although Kangave was never formally charged and no evidence was presented to Pride that he had taken Brian White’s money, his employer treated the allegations as a serious reputational risk.

Kangave challenged his dismissal in court.

Select Garments was evicted from Forest Mall. Court awarded it Shs1 billion

In court, Pride Microfinance (which has since transformed into Pride Bank) admitted that the decision to dismiss Kangave was connected to the allegations made by Brian White. The bank insisted that it had to protect its reputation because it handles public deposits and could not take risks with staff who were being investigated for possible wrongdoing.

The financial institution’s lawyers argued that the employer has the right to terminate an employee with notice. They said the meeting on March 25 gave Kangave a chance to explain himself. They insisted that the bank had acted in good faith by paying three months’ salary in lieu of notice.

They said the bank had a reasonable belief that the allegations against Kangave could damage its credibility.

Kangave’s lawyers told the court that he had served the bank faithfully for 16 years and had never been subjected to disciplinary action. They argued that the bank did not conduct an investigation, did not present evidence against him, did not summon him for a disciplinary hearing, and did not allow him to call witnesses or be represented. They said the termination was rushed, unlawful, and amounted to unfair labour practice.

They relied on the bank’s Human Resource Manual, the Employment Act, and previous Industrial Court decisions, which require an employer to prove both the reason for dismissal and the fairness of the procedure.

Court decides

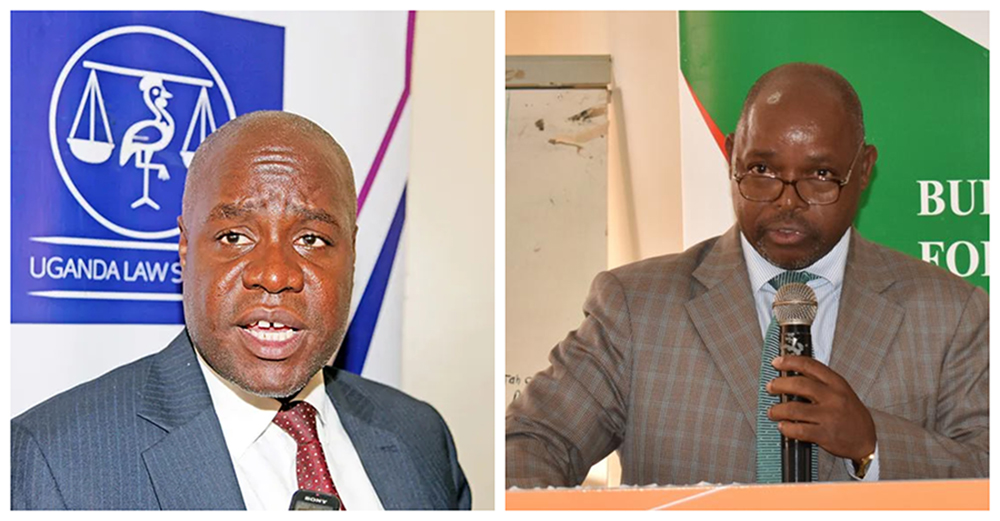

After hearing both parties, the court, led by Justice Anthony Wabwire Musana, rejected Pride Microfinance’s defence. It found that the March 25 meeting was not a disciplinary hearing. Musana said that the letter inviting Kangave was only an invitation to a meeting, not a formal charge sheet.

The court also noted that the bank had no investigation report. There were no witness statements. There were no minutes of any disciplinary session. There was no documented evidence shared with Kangave.

Musana said that discontinuing the disciplinary process and then issuing a termination letter on the same day was a “disguised dismissal” designed to appear lawful but lacking substance.

He concluded that the dismissal was “procedurally unfair” and “unlawful”.

The court also observed that the bank placed unrealistic demands on Kangave, such as obtaining a police clearance in just a few days, even though police processes take much longer.

“Even if an employer believes there is a reputational risk, it must still follow the law and its own procedures. It is no longer fashionable for employers to dismiss employees without any justification, even if the employee is paid in lieu of notice,” Musana wrote.

The court ordered the bank to pay Kangave more than Shs 146 million in severance, general damages, aggravated damages, salary in lieu of notice, and other payments.

Musana said the award was necessary, given the long service Kangave had rendered and the harm caused to his career and reputation. He emphasised that workers should not lose their livelihoods based on suspicion.