In July, Uganda agreed to take on an unspecified number of third-country nationals who have a pending asylum claim in the US but cannot return home due to safety concerns.

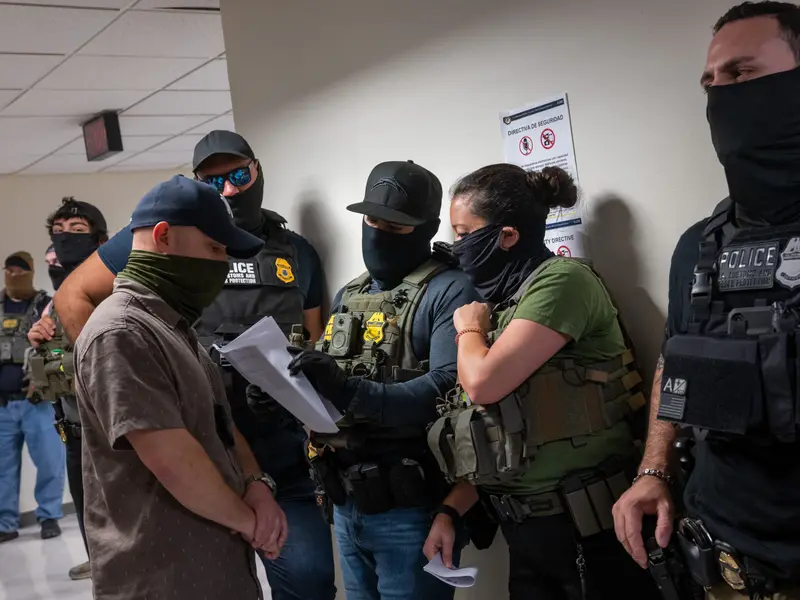

In other words, these are people who should likely be protected as refugees, but are no longer wanted in Donald Trump’s America.

According to the official Ugandan statement, the deal does not include people with a criminal background or unaccompanied minors. The written agreement, however, only mentions minors.

Once in Uganda, each person will go through individual refugee status determination processes.

The US-Uganda deal follows similar bilateral agreements with other African countries from recent weeks. For instance, eight people with a criminal background were deported in July to South Sudan.

Five similar cases were deported to Eswatini. In mid-September, Ghana became the latest African country to crumble, taking in 14 deported migrants from the US.

These agreements have usually been accompanied by much fanfare and followed by little in the way of receiving of actual refugees. Most recently Rwanda agreed to take in 250 people from the US. The first seven arrived in late August.

What are the issues with these arrangements?

The US is not alone in its attempts to send asylum seekers to countries in Africa. Plans – with varying levels of concreteness – have been thrown around by politicians from the UK, Denmark and Germany.

Migration is being demonised by politicians all over the world. So externalising, which basically means moving the location of the problem, may seem like a solution.

But African countries have not always received such offers with open arms. While global asymmetries and aid dependencies mean that African officials may not overtly reject such deal attempts, countries are not keen to take on any deportees, let alone from third countries.

In fact, there is no international convention that provides a legal instrument for deporting people from another nationality to a different country. International agreements, most recently the Samoa Agreement between the European Union and Africa, Caribbean and Pacific states, have removed the potential to deport third nationals.

Deporting nationals from other countries to African countries is, therefore, legally questionable – and diplomatically unpopular. The African Union has condemned such arrangements as “xenophobic and completely unacceptable”.

What’s in it for Uganda?

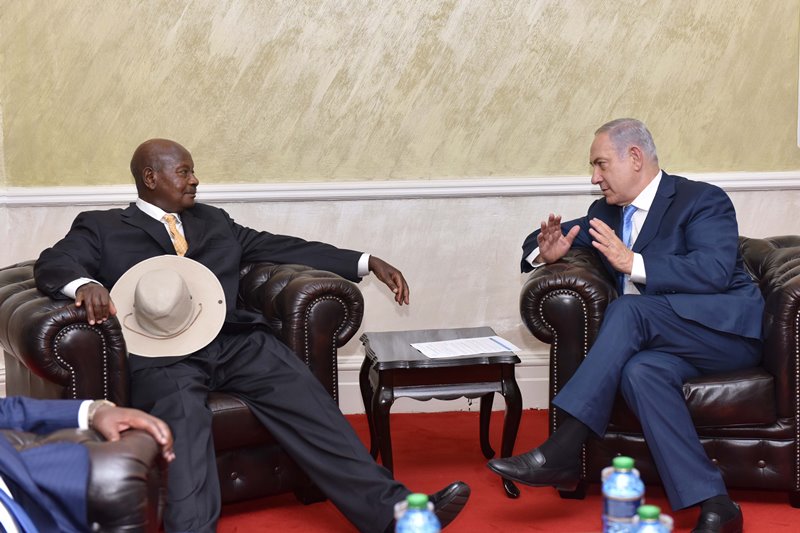

The deal provides the groundwork for much-needed improvements in bilateral US-Ugandan relationship.

In response to the globally condemned 2023 Anti-Homosexuality Act, the Joe Biden administration terminated Uganda’s eligibility for US trade benefits under the African Growth and Opportunity Act. This policy gave Uganda duty-free access to the American market for a variety of goods.

More recently under the Trump administration, Uganda has suffered the effect of US funding cuts. This includes the loss of an estimated 66% of funding following cuts to the USAID development assistance programme. Uganda also faces a higher tariff of 15%, up from the previously announced 10% that will affect the cost of its agricultural products in the US market. This could potentially lower its sales in a key export market.

While the details of the US-Uganda asylum deal are shrouded in secrecy, as is common with such agreements it could provide Uganda with much needed development funds and lead to better tariff conditions.

Domestically, opposition politicians have criticised the new bilateral deal. However, Museveni has not shown much concern for these misgivings. Uganda is one of the few countries where refugees have not become a major political issue.

As refugee numbers rise, conflicts between them and host communities over land and environmental damage are increasing. There is growing public apprehension about the government’s open-door policy.

Uganda has a long history of refugee protection. It currently hosts 1.8 million refugees and asylum seekers, mainly from South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The country has a reputation as one of the most generous places towards refugees. Most people entering Uganda are given automatic refugee status. This was set up in the 1969 refugee convention from the then Organisation of African Unity.

In practice, refugees are confined to dusty so-called refugee settlements, with few working and educational possibilities. Many refugees – just like the Ugandan host community – live under very high levels of poverty.

Will the refugees from US get the same treatment?

We do not know at this stage. However, in August 2021, Uganda agreed to take on up to 2,000 refugees from Afghanistan on behalf of the US. While this was deemed only a temporary move before they were resettled elsewhere, many remain in Uganda to this day.

Ugandans say refugees are our brothers and sisters. That is why our door will always be open to them.

The agreement reveals no details about their temporary housing or refugee status determination process. Whether they will be sent to the remote settlements where most refugees in Uganda access free housing and humanitarian assistance, or stay in urban Kampala, remains to be determined.

With elections in Uganda scheduled for January 2026, such a deal certainly helps President Yoweri Museveni preempt any US criticism regarding electoral freedom. But it also raises deeper questions about the long-term effects of open-door policies.