In his book Adults in the Room: My Battle with Europe’s Deep Establishment, Yanis Varoufakis, the Greek economist who served as Finance Minister during Greece’s greatest financial crisis, recalls a defining moment:

“When I entered the ornate meeting room in Brussels, the afternoon sun glinted off the polished maple table, casting long, sharp shadows across the documents arrayed before me. Across from me sat the president of the Eurogroup, flanked by his advisors, silent and composed. The air smelled faintly of expensive coffee and tension.

I placed our reform proposal before them. I could see, in their eyes, that they had already decided not to read it with open minds. They were not interested in negotiation; they were interested in maintaining control.

‘We propose a fundamental restructuring of debt, not the endless refinancing you’ve offered us till now,’ I said. ‘Greece cannot borrow to pay interest on itself. You ask us to bleed so that the banks in Frankfurt and Paris survive.’

The silence that followed was real, thick, and deliberate. One of the officials cleared his throat and spoke of stability, credibility, institutions, and in every phrase, I heard the same refrain: we must protect the system.

In that moment, I felt the weight of the Greek people behind me, those waiting for their pensions, their medical care, their children’s future. And I realized that unless we pushed beyond formal language, we would forever be trapped in the calculus of austerity.”

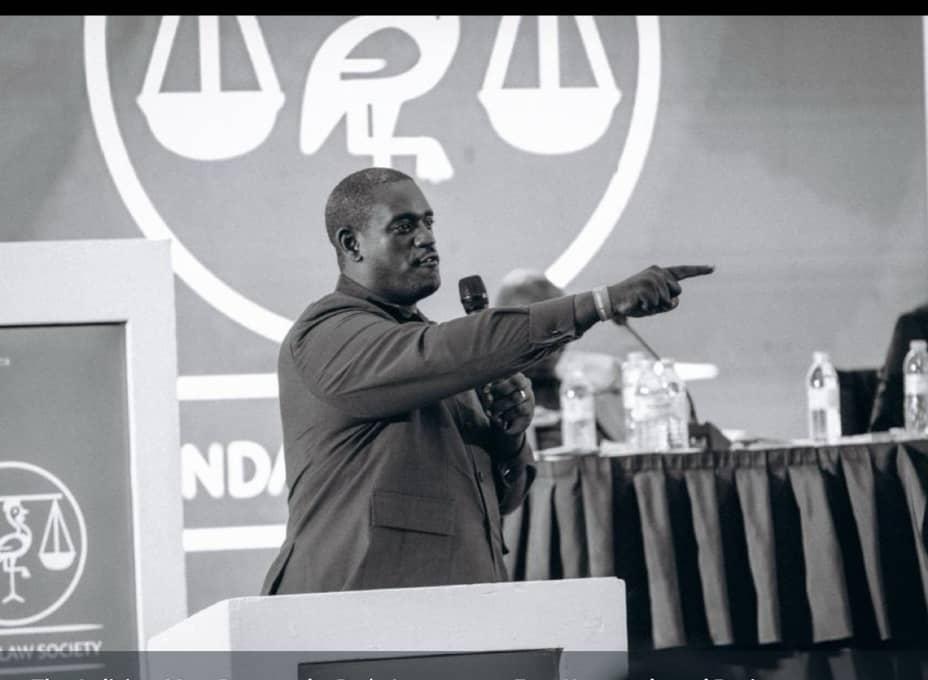

This morning, at 9:00 a.m., the High Court of Uganda at Kampala (Civil Division) will hear Miscellaneous Application No… of 2025, Tonny Tumukunde and Another v. Uganda Law Society, seeking to halt the implementation of resolutions passed by the membership of the Uganda Law Society at its September 2025 meeting at the Imperial Royale Hotel.

At this moment, I am reminded of Varoufakis’ reflection. Unless we, as the Bar, move beyond comfort and caution, we risk being trapped in the very structures we were meant to strengthen.

The Courts must allow the Bar to speak freely. For it is from the Bar that Magistrates and Judges are drawn. The Bar is the living reserve of the Bench; even in retirement, many judicial officers return to its fold. A muted Bar weakens mentorship, erodes the critical voice of the profession, and diminishes the renewal of talent upon which the Bench depends.

Each time we stand before the Bench, we sense the carved wood, the hush, and the weight of precedent. Yet behind that solemnity lies a deeper tension between inclusion and control. When the Bar is asked merely to assent in silence rather than to participate meaningfully, we risk turning dialogue into ritual.

The Bar must not be relegated to silence.

Article 146 of the Constitution of Uganda creates the Judicial Service Commission and entrusts it with the duty to “ensure and strengthen the independence and accountability of the Judiciary.”

It goes further, under Article 146(2)(c), to require two members of the Uganda Law Society (ULS) to serve on that Commission. This is not an act of generosity by the State. It is a constitutional command, a deliberate safeguard to ensure that the voice of the practicing Bar informs the conscience of the Bench.

The continued resort to injunctions to prevent the Uganda Law Society from fulfilling this constitutional role is a profound misdirection of judicial power. It frustrates the very balance the framers sought to achieve. For the Bar’s representation on the Judicial Service Commission is not an elective indulgence; it is an institutional necessity. Without it, the Commission is incomplete and its legitimacy diminished.

An injunction, properly understood, is a shield against irreparable harm, not a weapon to paralyse constitutional organs. To use it repeatedly to silence the Bar is to turn equity into restraint and to suspend the democratic principle that those governed by law must also participate in shaping it.

The Constitution intended that the Bar and Bench walk side by side, one speaking truth to the other, both serving justice together. When one side is gagged by procedural devices, the other is deprived of counsel, perspective, and renewal. It is not the Bar alone that suffers; it is justice itself.

No institution, however noble, can endure if its foundation is silenced. The Bench draws its strength not only from authority but from trust, and that trust is replenished when the Bar is allowed to speak, question, and contribute freely.

Let us therefore insist, with quiet firmness and constitutional fidelity, that the Bar’s representation on the Judicial Service Commission must not be stopped by injunction after injunction. The Constitution speaks with clarity; its voice must be obeyed.

Let us then be the Adults in the Room, steady in our conviction, calm in our reasoning, and unwavering in our duty to uphold the dialogue that sustains both the Bar and the Bench.

The author is a partner at KAA Advocates