The High Court has declared part of a lawsuit invalid because it was filed against a person who had already died. The case revolves around a piece of land in Kawempe, Kampala, measuring about five acres.

This land was subdivided into Plots 498 and 499 in the 1990s, sparking claims of fraud and ownership battles that have dragged on for over 15 years.

Genesis

The lawsuit began in 2010 when lawyers John W. Katende and Fredrick Ssempebwa sued Susan Ddamba and the late Ssendagire Abdul, accusing them of illegally subdividing and claiming the land.

Katende and Ssempebwa say they bought the original plot in the 1980s from John Sendagire and were registered as owners in 1985. They allege the subdivision happened without their consent in 1990, and they placed a “caveat” in 2008 to protect their interests.

Ddamba, however, tells a different story. In her court affidavit, she explains that in 1995, she bought the land from Semu Ntulume Nsibirwa (Ssendagire Abdul’s uncle). The land had squatters so she sold half (2.5 acres, becoming Plot 498) to Ssendagire Abdul to raise money to compensate them. She kept the other half (Plot 499) and says she’s lived there peacefully for 30 years, growing crops and eucalyptus trees.

Nanvuma Faridah Ssendagire, daughter of the late Ssendagire Abdul (who died in 2002), supported Ddamba’s application. She confirmed her father acquired Plot 498 in 1995 and that the family has managed it since his death. Letters of administration were granted to the family in 2013.

Katende and Ssempebwa tried to settle out of court, demanding Shs 200 million to remove the caveat, later raising it to Shs 300 million. Negotiations failed, and Ddamba and Nanvuma learned of the lawsuit only in 2021 when trying to sell or transfer parts of the land.

The original suit proceeded “ex parte” because the court allowed “substituted service” ( such as notifying via newspaper ads) after Katende and Ssempebwa claimed they couldn’t find Ddamba or Ssendagire Abdul. The case was dismissed in 2022 for lack of progress which allowed Ddamba to remove the caveat and subdivide her plot further.

But Katende and Ssempebwa reinstated the suit without properly notifying Ddamba. She only discovered this in May 2025 when court officials visited the land. Shocked, Ddamba filed an application to challenge the proceedings, arguing that the suit was invalid against Ssendagire Abdul since he died eight years before it was filed in 2010.

She was never properly served, despite living on the land with a caretaker and being known to local authorities.

In response, Katende and Ssempebwa argued Ddamba knew about the suit but delayed filing a defence, and there was no record of Ssendagire Abdul’s death at the lands ministry. He accused her of fraudulently subdividing the land after the dismissal.

Ruling

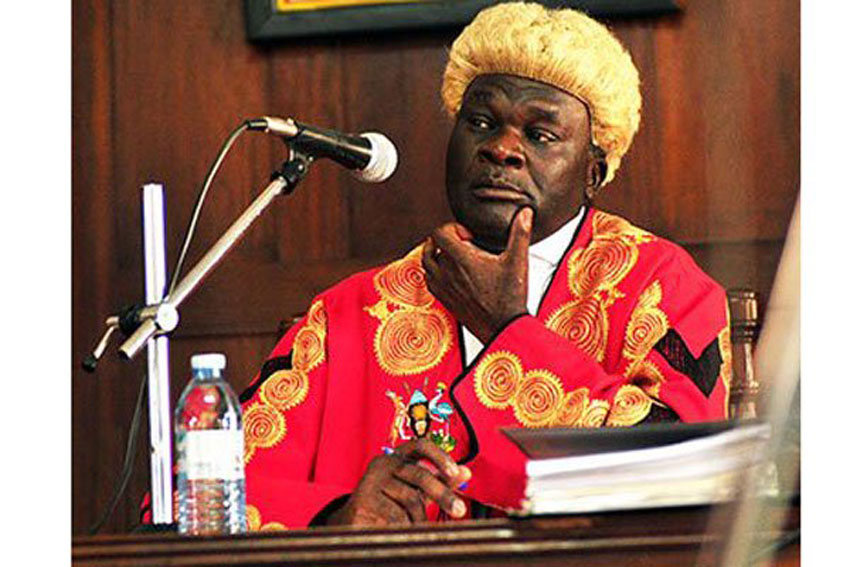

In a ruling yesterday, Justice Naluzze Aisha Batala argued that suing a deceased person makes the case a “nullity” – legally void from the start.

“A dead person is not a legal person,” she explained, citing Ugandan civil procedure rules. Unlike cases where someone dies during a lawsuit (where heirs can step in), a suit started against a dead person can’t be fixed by amendment. As a result, the court struck out the claims against the late Ssendagire Abdul.

For Ddamba, the judge found the ex parte proceedings unfair. Evidence showed she could have been easily located on the land, and that Katende and Ssempebwa had met her during negotiations but still didn’t serve her properly when reinstating the case.

Using the court’s inherent powers to ensure justice, Batala set aside the ex parte orders, emphasizing everyone’s right to a fair hearing under Uganda’s Constitution (Article 28).

Ddamba was given 21 days to file her written statement of defence, allowing the main suit to proceed on its merits.