The Constitutional Court has thrown out a public interest lawsuit aimed at stopping security agencies from re-arresting suspects immediately after they are granted bail, acquitted, or released by courts.

The court said the case doesn’t require interpreting the Constitution but is better suited for the High Court to handle as a human rights enforcement matter.

The petition was filed in 2019 by the Centre for Public Interest Law (CEPIL), a non-profit organization dedicated to promoting the rule of law and constitutional values.

CEPIL argued that between 2016 and 2019, security forces including police, military, and intelligence agencies repeatedly re-arrested suspects right on court premises, undermining court decisions and eroding public trust in the justice system.

CEPIL claimed these re-arrests violated key constitutional rights, such as the right to a fair trial, protection from torture or degrading treatment, and the independence of the judiciary.

The group listed seven specific incidents to back their claims, including:

- The 2016 re-arrest of five men acquitted of terrorism charges after a full trial.

- The 2017 re-arrest of suspects in Gulu after charges were dropped.

- The violent 2019 re-arrest of four suspects in the murder of police official Andrew Felix Kaweesi, along with their lawyer, James Mubiru, right after they got bail from the High Court’s International Crimes Division.

CEPIL also accused the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) alongside the Attorney General of helping these re-arrests by hiding new charges during bail hearings and then using them to keep suspects detained.

They said this abused the legal process and went against the DPP’s duty to act in the interest of justice. The petitioners asked the court for strong remedies.

In their defence, the Attorney General and DPP called the petition “frivolous” and an “abuse of court process.” They argued the re-arrests were legal and that the case was really about enforcing human rights, not interpreting unclear parts of the Constitution.

State Attorney Brian Musota said such issues belong in the High Court through judicial review or human rights applications.

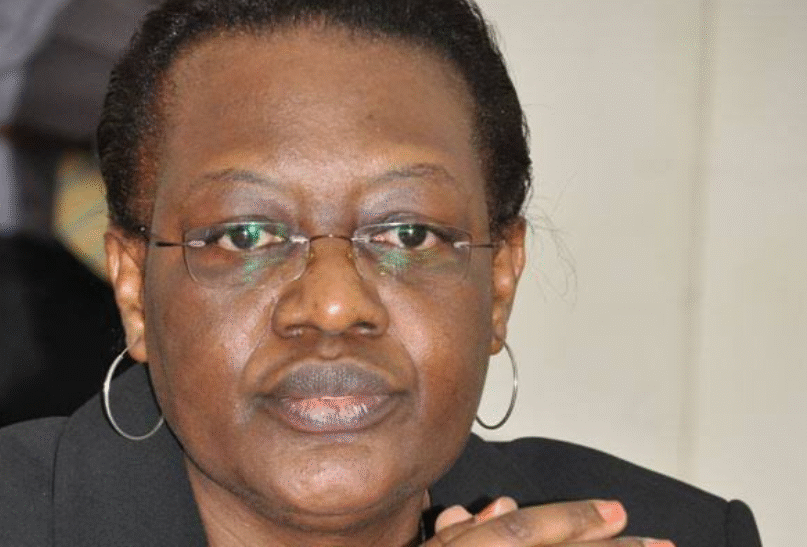

In the lead judgment, Justice Irene Mulyagonja agreed with the government. She explained the difference between a “cause of action” and “jurisdiction” (a court’s legal authority to hear a case). While CEPIL had a strong cause, the re-arrests clearly seemed to violate rights like freedom from arbitrary detention, the Constitutional Court can only step in if it needs to interpret ambiguous constitutional provisions.

“The jurisdiction of the Constitutional Court is confined to interpretation of the Constitution,” Justice Mulyagonja wrote, citing past Supreme Court rulings like Attorney General v. Major General David Tinyefuza (1997).

She noted that the rights in question, such as those under Articles 23 (right to bail), 28 (fair hearing), and 128 (judicial independence), are straightforward and don’t need new interpretation. Instead, victims could seek redress under Article 50, which deals with human rights enforcement in the High Court.

The other four judges – Geoffrey Kiryabwire, Christopher Gashirabake, Eva Luswata, and Oscar Kihika – all concurred, dismissing the petition without ordering costs, recognizing it was filed in the public interest.

However, the court’s decision doesn’t mean the re-arrests were lawful. It just says the wrong court was approached.

CEPIL’s Programmes Officer, Francis Obonyo, who provided evidence in the case, had referenced reports from the Uganda Human Rights Commission, the Chief Justice, and international groups decrying these practices.

But the court didn’t delve into those, as it ruled on jurisdiction first.