She fit right into the beauty stereotype: full lips, white teeth, smooth light chocolate skin. Her father died from HIV when she was too young to remember. Her mother remarried and was too busy rebuilding her life. The only way to occupy the perpetual emptiness she felt was to get a boyfriend at 15.

“No one ever told me anything. I was free to do whatever I wanted. I made my own decisions,” Ritah Alowo, now 35, recalls.

At 16, while in her second year of high school, she found herself with inaccurate contraceptive information and a pregnancy she was too scared to terminate.

“That day, we agreed to use condoms instead of the pills I used to take within 72 hours after sex,” she recalls. “But when we were finishing the game, the condoms broke. I saw, but I told myself, ‘those things did not enter me’.”

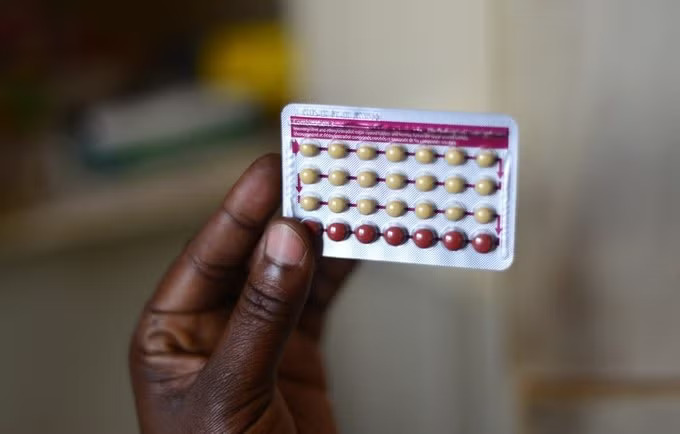

Health Policy Watch notes that in the face of policies restricting teenagers from accessing contraceptives, they turn to emergency contraceptives, which are more accessible, for long-term birth control.

“I had used emergency pills many times. Sometimes they would refuse to sell to me, and I would send my boyfriend to get them. They never refused to give them to him. It is difficult to walk in each time to buy emergency pills. Sometimes you wait for everyone to leave the pharmacy before asking for them,” Alowo says.

Restrictive policies have also contributed to the dire environment where one in five girls in Africa gets pregnant before they are 19. In 24 African countries, including Uganda, this figure rises to 1 in 5.

Sex is a mysterious topic spoken about in hushed tones – with religious and cultural protagonists, despite a court decision directing the government to provide sex education, mobilizing followers and influencing policymakers to block sex education. When teenage girls get pregnant, society treats it like an unfortunate event that they should bear the consequences of, while pardoning or ignoring the boys and men responsible for the pregnancy.

“I did not know that what we were doing would result in pregnancy. It was like a game to us. I was 14 and he was 15. I knew sex might result in pregnancy because we learned about it briefly at school, but I thought we were too young,” Doreen Nalumu, now 37 and a mother of five, recalls.

She had her baby 22 years ago with a boy who wooed her with lollipops and the deep-fried pastry namungodi. “I was living with my grandmother, who helped me hide the pregnancy from my parents. Both my parents were in the army, and my grandmother knew they would kill me if they found out.”

Nalumu’s baby girl left her with tares that still make her shudder when she thinks about them, and a limp that lasted years. The World Health Organisation highlights that teenage pregnancy is linked with higher morbidity and mortality rates.

It is the number one killer of girls aged 15 to 19. Despite the stigma and complications of her pregnancy, Nalumu was pregnant again two years later at 17. The same boy was responsible. The baby died after four days. Her parents vowed not to take her back to school.

“Even after my first baby, no one gave me information about sex or contraceptives. I walked out of the hospital with nothing. After the second baby, my parents blamed me. They said I had failed to learn my lesson the first time, and they refused to give me another chance,” Nalumu says with resignation, adding that she still believes that it is her fault she never got to achieve her dream of becoming a political leader.

The guilt of a teenage pregnancy lasts for a long time. The girls accept the loss of their dreams as a fair price to pay for the disappointment and shame that they cause.

When Alowo speaks to me from Jordan, where she moved from Uganda to do domestic work, she remembers ruefully how badly she wanted to be a broadcast journalist.

“I wanted to be on TV asking people questions. Now I am here doing this work of ours,” Alowo says. She cannot bring herself to spell out what she does. The pain hangs across the line as someone shouts over her in Arabic. She whispers that she has to hang up soon. I ask her to answer one last question: Would her life have been different if she had had access and proper information and contraceptives?

“Of course,” her reply is prompt. “I wish someone had told me how to control myself, how to prevent pregnancy. I wish someone had talked to me.”

Rwanda Healthcare Service Bill, passed in August, recognizes the rights of teenagers as young as 15 to access contraceptives even without the consent of parents, enabling girls to have more access to information and agency over their bodies.

“Rwanda is waking up to face the reality that teenagers are having sex and they need the information to protect themselves,” Joy Asasira, lawyer and human rights activist, says.

“People argue that it is not African to give girls access to contraceptives, but Rwanda has shown that protecting girls’ health and dreams is more important than an uncertain African culture that has failed to protect girls from the

unimpeachable men who get them pregnant.”

This is a good story but the promoters should understand that in Africa and Uganda specifically, sex education didn’t. mean contraceptive, no. Rather it is the know how of how one protects themselves from such behavior considered dangerous.