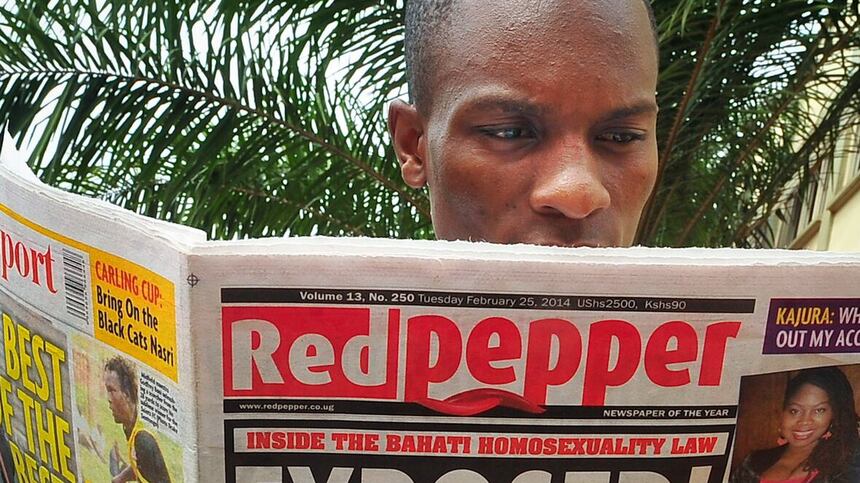

If you came of age in the early 2000s in Uganda, one tabloid stood out like the fiery chilli it claimed to be: The Red Pepper. If you wanted the juiciest scoops on celebrities, politicians, and everyday personalities, Red Pepper was your go-to source. It had been christened Kamulali in the local dialect, a direct translation of its title.

Founded by a group of young, energetic journalists led by Richard Tusiime, this paper was not just ink on paper—it was the heartbeat of Uganda’s gossip scene. It shattered taboos, diving headfirst into topics like sex that mainstream media outlets like New Vision and Daily Monitor shied away from, making it essential reading for anyone craving unfiltered truth mixed with a dash of scandal (who remembers the public outcry surrounding the photo it carried of half-naked teens making out at a beach party in Entebbe?)

Back then, picking up a copy of Red Pepper felt like unlocking a secret diary of the nation’s elite. Picture this: office workers huddled around a single issue during breaks, chuckling over exposés that peeled back the curtains on high-society dramas.

Politicians trembled at the thought of landing on its front page, while celebrities (like Karitas Karisimbi) either courted its attention or cursed its name. It sparked conversations, breaking barriers on sensitive issues that Ugandan society had long swept under the carpet. Sex education? Mr Hyena? Celebrity affairs? Political intrigue? Red Pepper served it all with unapologetic flair, and sometimes, an arrogant tone.

But like a party that rages too hard, Red Pepper’s glory days couldn’t last forever. After 2016, the cracks began to show. The tabloid faced a barrage of challenges that eroded its empire.

Legal Battles

At the core of these woes were defamation lawsuits—legal battles where powerful figures accused the paper of tarnishing their reputations. These weren’t minor skirmishes; they were full-blown wars that drained Red Pepper’s coffers and sapped its spirit.

One of the most high-profile defamation lawsuits came from Samuel Wako Wambuzi, the former Chief Justice. In 2017, Wambuzi sued Red Pepper over an article that allegedly portrayed him in a false light, linking him to corrupt dealings. The court didn’t hold back.

Justice Patricia Basaza Wasswa ruled that the publication had indeed libelled Wambuzi, ordering Red Pepper to pay a staggering Shs 425 million in damages. This included 300 million in general damages, Shs 100 million in exemplary damages to deter future recklessness, and 25 million in aggravated damages for the emotional toll. Red Pepper appealed the decision, but in 2020, the Court of Appeal upheld most of the ruling, only tweaking minor aspects.

The financial blow was immense; paying out such sums meant diverting funds from operations, salaries, and printing costs. It’s like a family business hit with a massive fine—suddenly, the lights flicker, and corners are cut just to stay afloat.

Not long before that, in 2016, Speaker of Parliament Rebecca Kadaga took Red Pepper to court over a story that she claimed defamed her character. The High Court sided with Kadaga, slapping the tabloid with a Shs 120 million payout. This case highlighted how Red Pepper’s sensational style often crossed into dangerous territory, accusing figures of misconduct without ironclad proof.

Dean Lubowa Saava: The firebrand journalist who enjoys dancing with controversy

The damages weren’t just a slap on the wrist; they represented months of revenue lost, forcing the paper to rethink its aggressive reporting.

Then there was the lawsuit from Best Kemigisa, the Queen Mother of Tooro Kingdom. In 2020, Justice Musa Ssekaana awarded her Shs 83 million after Red Pepper published articles linking her to a fake dollar scandal. The court found the stories defamatory, noting how they lowered her esteem in the eyes of right-thinking members of society. This payout added to the growing pile of financial burdens, eating into profits and making it harder for Red Pepper to invest in quality journalism.

Even international figures were not spared; in 2009, the tabloid was charged with defaming the Libyan president.

Although it won some of them, the cumulative effect of these lawsuits was devastating. These payouts, often running into hundreds of millions of shillings, forced the tabloid to cut staff, reduce print runs, and even delay payments to suppliers.

Compounding these legal woes was a brief but brutal shutdown in November 2017. The government raided Red Pepper’s offices in Namanve over a story alleging tensions between Uganda and Rwanda, accusing the paper of publishing information prejudicial to state security.

Editors and owners were arrested, and operations halted for months. This was notjust a pause; it was a body blow that cost the paper dearly in lost revenue and credibility. Star reporters like John Sserwaniko and Henry Mulindwa jumped ship, starting their own online ventures, leaving Red Pepper’s newsroom a shell of its former self. The exodus of reporters was like that of rats fleeing a sinking ship.

Rise of social media

Yet perhaps the biggest thief of Red Pepper’s thunder was the rise of social media. Platforms like Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), and TikTok exploded in Uganda after 2015, offering instant gossip at the tap of a screen. Why wait for a newspaper when you could scroll through viral posts, memes, and live videos dishing dirt on the same celebrities and politicians?

Social media’s speed and accessibility ate into Red Pepper’s gossip territory like termites devouring a wooden house—slowly but surely, weakening the foundation until the structure crumbles.

For Red Pepper, this meant losing readers who once relied on its pages for scandalous scoops. Now, anyone with a smartphone could become a citizen journalist, sharing rumours faster than the tabloid could print them. The exponential growth of these platforms didn’t just compete; it redefined the game, turning Red Pepper from a “kingpin” to a “has-been”. Nostalgic fans recall flicking through its colourful pages, but today’s youth prefer the endless feed of TikTok dances and X threads.

Today, Red Pepper limps along, appearing sporadically in print and focusing mostly on online content. It is a far cry from its heyday, when it ruled the gossip world with an iron fist wrapped in sensational headlines.

In an era of filtered Instagram lives and fleeting tweets, some of us miss that raw, unpolished spice Red Pepper brought to Uganda’s social conversations at the office, in a pub, at a wedding, or even at a funeral.